Key Findings and Recommendations

The Mara Predator Conservation Programme works closely with conservation management bodies and related stakeholders, taking key findings from our work and making evidence-based recommendations that can inform conservation strategy across the Greater Mara ecosystem, and sometimes beyond.

Key Finding: Baseline Data

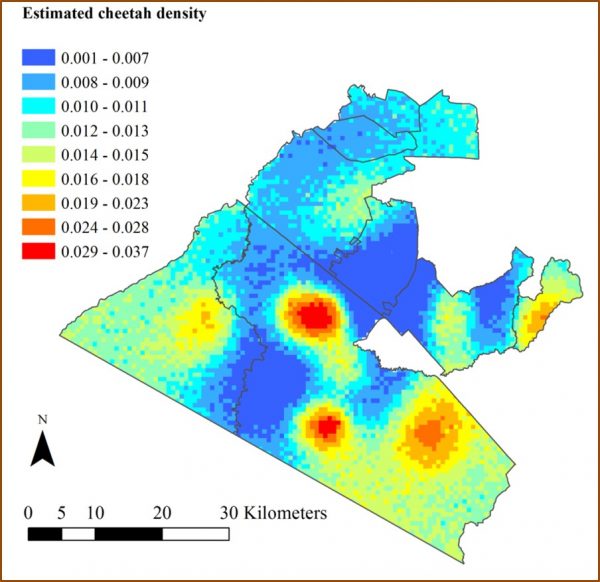

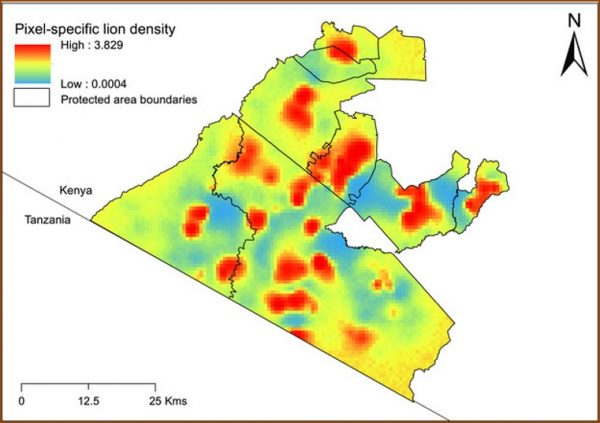

Our first lion and cheetah baseline survey was conducted during our second intensive monitoring period of 2014. These data were then analysed by our team within a Spatially Explicit Capture Recapture framework. The results showed an overall lion density in the study area of 16.85 lions per 100km2 over the age of one year. This translates to 420 lions. The results for cheetahs were much lower, giving only 1.27 adult cheetahs/100km2 in the study area (roughly 31 adults). However, these figures are higher than many places in Africa, demonstrating how crucial the Greater Mara ecosystem is to the long-term survival of both predator populations. Our spatially explicit approach estimates density at a very fine scale and therefore provides a ‘heatmap’ of high and low species density, which can be seen below for both lion and cheetah:

Broekhuis, F., & Gopalaswamy, A. M. (2016). Counting cats: spatially explicit population estimates of cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) using unstructured sampling data. PloS one, 11(5), e0153875.

Key Finding: Conservancy Effect

We have found over the past four years that each community conservancy (a protected area, like the Maasai Mara National Reserve) where we monitor wildlife has a high lion density at its core. Closer to the boundary of a conservancy (or the Reserve), the density is lower. This “edge effect” is most likely indicative of human disturbance. Human settlements around the boundaries of these protected areas may help to explain why lion density is high in the cores, yet low on the edges. A second, related explanation could be that the cores are better protected from livestock incursions.

Recommendation:

The core parts of each protected area are vital to maintaining healthy lion numbers. However, the boundaries (both of conservancies and the Reserve) require significant and sustainable management attention, if we are to see lion numbers increasing in these areas. We would also likely see a reduction in human-lion conflicts if boundaries were better protected and/or enforced.

Key Finding: Lion Density

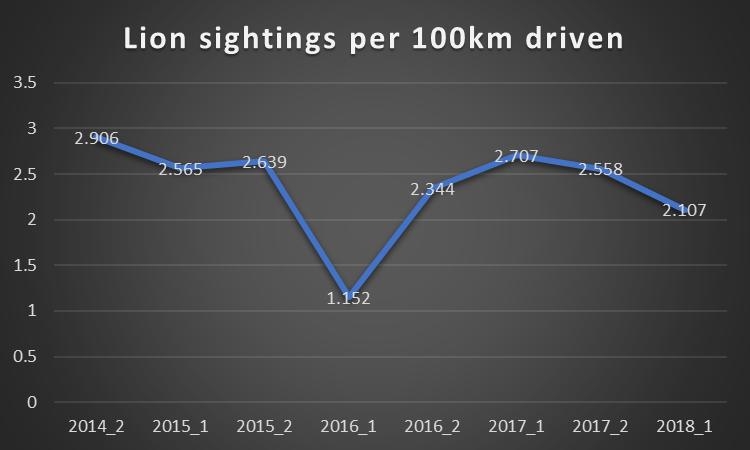

Every year we undertake two intensive monitoring sessions, or surveys. These 90 day sessions represent two very different periods; the first is during the Serengeti wildebeest migration (August to October), and the second is outside the migration (February to April). We have found that this length of survey period is ideal to ensure population closure of all wildlife we monitor. This enables us to understand specific population trends and use our data to inform conservation strategy.

We have completed eight survey periods since we started our fieldwork. We continue to analyse all the data captured, and the graph shown below provides some insight into what we are discovering.

For example, in the first intensive monitoring period of 2016 (February-April) we saw a reduction in the number of lion sightings per 100 km driven. This period was characterized by particularly tall grass, meaning that lions were inevitably harder to find. For this reason, we are further analyzing these data alongside the data from the second intensive monitoring period of 2014, to assess whether or not the population has truly suffered losses.

Recommendation:

In order to truly understand lion population trends, long-term and consistent monitoring is required. Wildlife populations can and do fluctuate naturally, depending on many environmental variables. Therefore, is it still too early to determine a true population trend in lions; more monitoring is required by our team using consistent methods for effective comparison year on year. Intensive monitoring requires a great deal of resource and support, both in terms of funds and in terms of continuous access to all protected areas. We thank everyone who has contributed in either way; thanks to them we can continue this vital conservation work.

Key Finding: Cheetah Habitat

Our long-term monitoring of cheetahs across the Greater Mara ecosystem has clearly shown that female cheetahs who are living and operating in areas with good cover (provided by acacia and croton) are more likely to raise more cubs per litter to adulthood.

Recommendation:

If the Mara’s cheetah population is to remain stable, the health of their habitat must be ensured. Conservation management should strive to ensure the availability of a mosaic of habitats across the Mara. This can be achieved by minimising conversion from bushland to grassland.

Key Finding: Livestock Protection

From the studies and community engagement work we have undertaken since 2013, it is apparent that depredation of sheep and goats (or ‘shoats’) is a significant challenge facing the Mara’s people and its wildlife. Our data shows that depredation of shoats by cheetah is most likely to occur outside bomas during the day, as either there are no herders present, or the herds are watched over by children (who do not have adequate husbandry experience to protect their charges).

Recommendation:

We work closely with the communities around the Mara to discuss and recommend good husbandry of all livestock (shoats and cattle). Good herding practices – such as having only adults herd livestock – should be continuously encouraged. We will continue to work with people on this important issue, as well as devising solutions to protect livestock from depredation e.g. building predator-proof bomas.

Key Finding: Retaliatory Killing

Through our community surveys undertaken over a number of years since we started our work in the Mara, we have found a clear link between retaliatory killing of predators and predisposed negative attitudes towards the same wildlife.

Recommendations:

Consistent management policies across conservancies need to be adopted, so as to involve community members more directly and relevantly in conservation management.

Additionally, we would like to see more people from the Mara being employed in the tourism industry, who have grown up with wildlife on their doorstep, rather than people from further afield. Local investment of this kind will give community members a more personal reason to protect predators, as they would benefit from them by virtue of their job.

Thirdly, we have found that community-based initiatives are not even-spread. We would like to see this improved, so that such initiatives reach more people, helping to build awareness of the importance of predators and protecting them. This, in turn, could help to reduce human-predator conflicts across the region.